- HOKC Newsletter

- Posts

- Torture Methods Of The Plains Tribes

Torture Methods Of The Plains Tribes

Torture Methods of the Plains Tribes

Among the Native tribes of the Great Plains—Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Sioux, Crow, and others—warfare was both a way of life and a deeply spiritual act. It was not simply about killing an enemy, but testing courage, honoring spirits, and achieving revenge for slain kin. Torture, while horrifying through modern eyes, was often carried out with ritual significance—meant to display bravery, punish cruelty, and ensure the enemy’s spirit would not return to haunt the living.

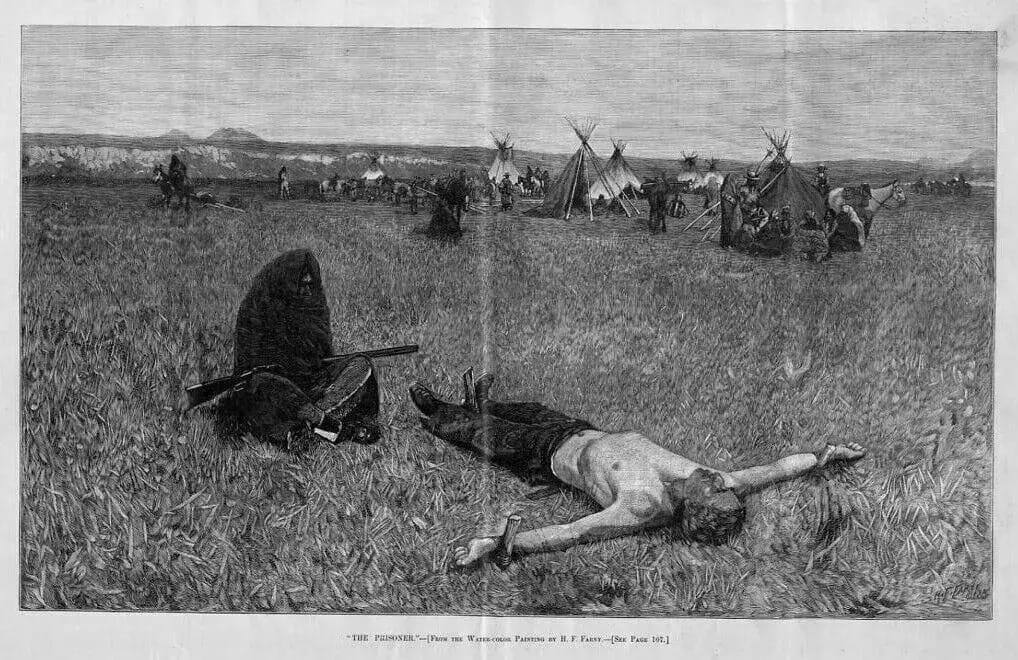

When a warrior was captured alive—usually after a raid or battle—he might be brought back to camp for ceremonial execution. The event was not a chaotic outburst of cruelty, but a public ritual involving the entire community. Women, in particular, often took part, especially if the captive’s tribe had killed their relatives. The captive’s endurance was a measure of both his worth and that of his enemies. Dying well, without crying out, was believed to earn honor even among his captors.

Among the Comanche, known for their ferocity and skill in war, torture was used to strike terror into enemies like the Texas Rangers or Tonkawa scouts. A common practice involved tying a captive spread-eagle to the ground or to a post. The scalp would be removed while the man still lived, and hot coals or burning pitch applied to the exposed skull. Comanches might cut off fingers, slice muscles, or mutilate genitals—each act punctuated with taunts, songs, or dances. Sometimes they would set small fires under the captive’s feet or chest, prolonging agony for hours. Horses were sometimes involved too—victims might be dragged behind them or tied to a stake where horses trampled the ground nearby. Yet, to the Comanche, this was not mere savagery—it was vengeance and theater combined, displaying dominance and feeding the spirits of slain relatives.

The Cheyenne also carried out elaborate tortures, often with spiritual overtones. Captives might be tied to a stake, and tribespeople would approach in sequence to cut, pierce, or burn portions of the body. Red-hot arrows were sometimes thrust into the flesh, and bones broken one by one. Some Cheyenne accounts describe captives being “painted for death,” with red and black warpaint applied before execution—a symbolic gesture marking their passage into the spirit world. Despite the horror, some victims were admired for their stoic silence. The Cheyenne believed that facing pain with courage allowed the soul to rise honorably after death.

The Sioux were known for similar practices, especially against tribal enemies like the Crow. One common method was to bind the captive to a stake surrounded by dry kindling, then slowly burn him while dancers circled, chanting war songs. Women often led the singing, sometimes wielding torches to light the fires themselves. The execution might last until dawn, with every stage witnessed by the camp.

Not all Plains tribes emphasized torture equally. The Crow, for instance, while fierce in war, were less inclined toward prolonged cruelty, favoring quick executions or adoption of captives. The Kiowa, however, like the Comanche, saw torture as part of vengeance and cosmic balance—a way to restore harmony through suffering.

Ultimately, torture among the Plains tribes cannot be separated from its cultural and religious framework. It served as punishment, retribution, and initiation—a public reaffirmation of strength and endurance in a violent world. To die without fear was to prove one’s spirit unbroken, even in defeat. To the people of the Plains, this was not madness—it was the ultimate test of courage, witnessed by gods and men alike.

To learn more about these gruesome methods, check out the HOKC episode linked below!